What Are The Four Varnas

Ancient India in the Vedic Period (c. 1500-1000 BCE) did not have social stratification based on socio-economic indicators; rather, citizens were classified according to their Varna or castes. 'Varna' defines the hereditary roots of a newborn, it indicates the color, blazon, guild or class of people. Four master categories are divers: Brahmins (priests, gurus, etc.), Kshatriyas (warriors, kings, administrators, etc.), Vaishyas (agriculturalists, traders, etc., likewise called Vysyas), and Shudras (labourers). Each Varna propounds specific life principles to follow; newborns are required to follow the customs, rules, conduct, and beliefs fundamental to their corresponding Varnas.

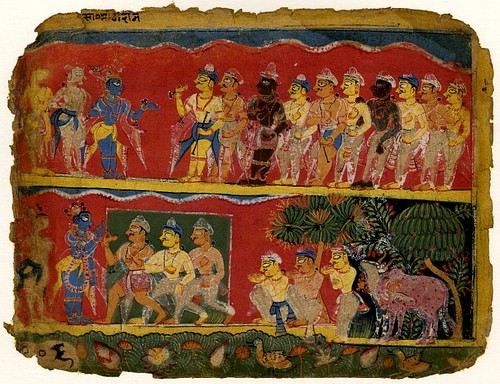

Bhagavata Purana

The first mention of Varna is found in the Purusha Suktam verse of the aboriginal Sanskrit Rig Veda. Purusha is the primordial being, constituted by the combination of the four Varnas. Brahmins plant its mouth, Kshatriyas its arms, Vaishyas its thighs, and Shudras its anxiety. As well, a society, too, is constituted by these four Varnas, who, through their obedience to the Varna rules, are provisioned to sustain prosperity and order. A newborn in a specific Varna is not mandatorily required to obey its life principles; individual interests and personal inclinations are attended upon with equal solemnity, so as to uproot the conflict between personal choice and customary rules. Given this freedom, a deviated choice is e'er assessed for its cascading impact on others. The rights of each Varna citizen are e'er equated with their individual responsibilities. An elaborated Varna system with insights and reasoning is constitute in the Manu Smriti (an aboriginal legal text from the Vedic Menses), and afterward in various Dharma Shastras. Varnas, in principle, are not lineages, considered as pure and indisputable, simply categories, thus inferring the precedence of conduct in determining a Varna instead of birth.

Purpose of the VARNA Organization

The degree system in ancient India had been executed and acknowledged during, and ever since, the Vedic period that thrived around 1500-yard BCE. The segregation of people based on their Varna was intended to decongest the responsibilities of one'southward life, preserve the purity of a degree, and institute eternal order. This would pre-resolve and avoid all forms of disputes originating from conflicts within business and encroachment on corresponding duties. In this system, specific tasks are designated to each Varna denizen. A Brahmin behaving every bit a Kshatriya or a Vaishya debases himself, becoming unworthy of seeking liberation or moksha. For a Brahmin (having become one by deed, in improver to the one by birth) is considered the club's mouth, and is the purest life form as per the Vedas, considering he personifies renunciation, austerity, piousness, striving simply for wisdom and cultivated intellect. A Kshatriya, too, is required to remain loyal to his Varna duty; if he fails, he could exist outcast. The same applies to Vaishyas and Shudras. Shudras, far from left out or irrelevant, are the base of an economy, a potent back up system of a prosperous economic system, provided they remain bars to their life duties and not give in to greed, immoral behave, and excess cocky-indulgence.

The underlying reason for adhering to Varna duties is the belief in the attainment of moksha on being dutiful.

The main thought is that such order in a society would pb to contentment, perpetual peace, wilful adherence to law, wilful deterrence from all misconduct, responsible exercise of freedom and freedom, and keeping the fundamental societal trait of 'shared prosperity' above all others. Practical and moral education of all Varnas and such order seemed justified in ancient Indian social club attributable to dissimilar Varnas living together and the possibility of disunity among them. Hence, Brahmins were entrusted with the duty of educating pupils of all Varnas to understand and do gild and mutual harmony, regardless of distressed circumstances. Justice, moral, and righteous behaviour were master teachings in Brahmins' ashrams (spiritual retreats, places to seek knowledge). Equipping pupils with a pure conscience to atomic number 82 a noble life was considered essential so was practical education to all Varnas, which provided students with their life purposes and knowledge of correct comport, which would manifest later into an orderly club.

Follow the states on Youtube!

The underlying reason for adhering to Varna duties is the belief in the attainment of moksha on being dutiful. Belief in the concept of Karma reinforces the belief in the Varna life principles. As per the Vedas, information technology is the ideal duty of a human to seek freedom from subsequent birth and expiry and rid oneself of the transmigration of the soul, and this is possible when one follows the duties and principles of one'southward corresponding Varna. According to the Vedas, consistent inroad on others' life responsibilities engenders an unstable society. Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras grade the fourfold nature of society, each assigned advisable life duties and ideal disposition. Men of the offset 3 hierarchical castes are called the twice-born; first, built-in of their parents, and second, of their guru after the sacred thread initiation they wear over their shoulders. The Varna arrangement is seemingly embryonic in the Vedas, later elaborated and amended in the Upanishads and Dharma Shastras.

Brahmins

Brahmins were revered as an incarnation of knowledge itself, endowed with the precepts and sermons to be discharged to all Varnas of lodge. They were not just revered because of their Brahmin birth but as well their renunciation of worldly life and cultivation of divine qualities, assumed to be always engrossed in the contemplation of Brahman, hence called Brahmins. Priests, gurus, rishis, teachers, and scholars constituted the Brahmin community. They would e'er live through the Brahmacharya (celibacy) vow ordained for them. Even married Brahmins were called Brahmachari (celibate) by virtue of having intercourse only for reproducing and remaining mentally detached from the deed. However, anyone from other Varnas could also become a Brahmin after all-encompassing acquisition of knowledge and tillage of one's intellect.

Brahmins were the foremost selection as tutors for the newborn because they represent the link between sublime noesis of the gods and the four Varnas. This manner, since the ancestral wisdom is sustained through guru-disciple do, all citizens born in each Varna would remain rooted to the requirements of their lives. Usually, Brahmins were the personification of contentment and dispellers of ignorance, leading all seekers to the zenith of supreme cognition, however, nether exceptions, they lived as warriors, traders, or agriculturists in astringent adversity. The ones bestowed with the titles of Brahma Rishi or Maha Rishi were requested to counsel kings and their kingdoms' administration. All Brahmin men were allowed to ally women of the first three Varnas, whereas marrying a Shudra adult female would, marginally, insufficient the Brahmin of his priestly status. Yet, a Shudra woman would non be rejected if the Brahmin consented.

The Vedas (Rig-veda)

Brahmin women, reverse to the popular belief of their subordination to their husbands, were, in fact, more revered for their chastity and treated with unequalled respect. As per Manu Smriti, a Brahmin adult female must just ally a Brahmin and no other, just she remains free to cull the man. She, nether rare circumstances, is allowed to marry a Kshatriya or a Vaishya, but marrying a Shudra man is restricted. The restrictions in inter-caste marriages are to avoid subsequent impurity of progeny born of the matches. A man of a particular caste marrying a woman of a higher caste is considered an imperfect match, culminating in ignoble offspring.

Kshatriyas

Kshatriyas constituted the warrior clan, the kings, rulers of territories, administrators, etc. It was paramount for a Kshatriya to be learned in weaponry, warfare, penance, austerity, administration, moral conduct, justice, and ruling. All Kshatriyas would be sent to a Brahmin's ashram from an early age until they became wholly equipped with requisite knowledge. Besides austerities like the Brahmins, they would gain additional knowledge of administration. Their cardinal duty was to protect their territory, defend against attacks, deliver justice, govern virtuously, and extend peace and happiness to all their subjects, and they would accept counsel in matters of territorial sovereignty and upstanding dilemmas from their Brahmin gurus. They were allowed to marry a woman of all Varnas with mutual consent. Although a Kshatriya or a Brahmin adult female would be the kickoff choice, Shudra women were not barred from marrying a Kshatriya.

Kshatriya women, like their male counterparts, were equipped with masculine disciplines, fully acquainted with warfare, rights to discharge duties in the king's absenteeism, and versed in the affairs of the kingdom. Contrary to popular belief, a Kshatriya woman was as capable of defending a kingdom in times of distress and imparting warfare skills to her descendants. The lineage of a Kshatriya king was kept pure to ensure continuity on the throne and merits sovereignty over territories.

Vaishyas

Vaishya is the third Varna represented by agriculturalists, traders, money lenders, and those involved in commerce. Vaishyas are also the twice-born and go to the Brahmins' ashram to learn the rules of a virtuous life and to refrain from intentional or adventitious misconduct. Cattle rearing was one of the most esteemed occupations of the Vaishyas, equally the possession and quality of a kingdom'due south cows, elephants, horses, and their upkeep afflicted the quality of life and the associated prosperity of the citizens. Vaishyas would work in shut coordination with the administrators of the kingdom to discuss, implement, and constantly upgrade the living standards past providing profitable economic prospects. Considering their life comport exposes them to objects of immediate gratification, their tendency to overlook the law and despise the weak is perceived as probable. Hence, the Kshatriya rex would exist nigh busy with resolving disputes originating of conflicts amid Vaishyas.

2 Traders in Discussion, Ajanta

Vaishya women, too, supported their husbands in concern, cattle rearing, and agriculture, and shared the burden of work. They were equally free to cull a spouse of their choice from the four Varnas, albeit selecting a Shudra was earnestly resisted. Vaishya women enjoyed protection under the law, and remarriage was undoubtedly normal, just equally in the other three Varnas. A Vaishya adult female had equal rights over bequeathed properties in case of the untimely death of her husband, and she would be equally liable for the upbringing of her children with back up from her husband.

Shudras

The last Varna represents the backbone of a prosperous economic system, in which they are revered for their dutiful conduct toward life duties ready out for them. Scholarly views on Shudras are the nearly varied since there seemingly are more restrictions on their conduct. However, Atharva Veda allows Shudras to hear and larn the Vedas by centre, and the Mahabharata, too, supports the inclusion of Shudras in ashrams and their learning the Vedas. Becoming officiating priests in sacrifices organised by kings was, however, to a large extent restricted. Shudras are non the twice-built-in, hence not required to habiliment the sacred thread like the other Varnas. A Shudra man was only allowed to marry a Shudra woman, but a Shudra woman was allowed to ally from any of the four Varnas.

Shudras would serve the Brahmins in their ashrams, Kshatriyas in their palaces and princely camps, and Vaishyas in their commercial activities. Although they are the feet of the primordial being, learned citizens of higher Varnas would always regard them as a crucial segment of guild, for an orderly society would be hands compromised if the anxiety are weak. Shudras, on the other mitt, obeyed the orders of their masters, considering their noesis of attaining moksha past embracing their prescribed duties encouraged them to remain loyal. Shudra women, as well, worked as attendants and close companions of the queen and would become with her subsequently marriage to other kingdoms. Many Shudras were as well allowed to be agriculturalists, traders, and enter occupations of Vaishyas. These detours of life duties would, notwithstanding, exist under special circumstances, on perceiving deteriorating economic situations. The Shudras' selflessness makes them worthy of unprecedented regard and respect.

Gradual withdrawal from the ancient Varna duties

Despite the life club existence bundled for all kinds of people, by the end of the Vedic period, many began to deflect and disobey their primary duties. Brahmins started to feel the authoritarian nature of their occupation and status, because of which arrogance seeped in. Many gurus, citing their advice-imparting position to Kshatriya kings, became unholy and deceitful by practising Shudra qualities. Although Brahmins are required only to live on alms and not seek more than than their minimal subsistence, capitalising on their superior status and unquestioned hierarchical outreach, they began to demand more for conducting sacrifices.

Kshatriyas contested with other kings often to brandish their prowess and possessions. Many kings found it acceptable to turn down their Brahmin guru's advice and hence became self-regulating, taking unrighteous decisions, leading to loss of kingship, territory, and the confidence of the Vaishyas and Shudras. Vaishyas started to see themselves as powerful in their ownership of state and subjection of Shudras. Infighting, deceit, cheating influenced the conduct of Vaishyas. Shudras were repeatedly oppressed by the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas at will, which made them disown their duties and instead opt for stealing, lying, avariciousness, and spreading misinformation.

India is now habitation to a repository of the primary iv Varnas & hundreds of sub-Varnas, making the original four Varnas merely 'umbrella terms' & perpetually ambiguous.

Thus, all Varnas barbarous from their virtuosity, and unrighteous acts of ane connected to inspire and justify similar acts of others. Mixing of castes was too considered a office of the declining interest in Varna system. About of these changes took place between 1000 BCE and 500 BCE when constant social and economic complexities emerged as new challenges for Varna-based allocation of duties. Population increased, and so did the disunity of citizens in their collective belief in the sanctity of the original Varna organization. Religious conversions played a significant part in subsuming big societies into the tenets of humanism and a single large society.

The period betwixt 300 CE to 700 CE marked the intersection of multiple religions. As a large Varna populace became hard to handle, the emergence of Jainism propounded the credo of one unmarried human Varna and nothing besides. Many followed the original Varna rules, but many others, disapproving opposing beliefs, formed modified sub-Varnas within the master four Varnas. This procedure, occurring between 700 CE and 1500 CE, continues to this day, equally India is now habitation to a repository of the primary four Varnas and hundreds of sub-Varnas, making the original four Varnas only 'umbrella terms' and perpetually cryptic.

The subsequent rise of Islam, Christianity, and other religions besides left their mark on the original Varna system in Bharat. Converted generations reformed their notion of Hinduism in ways that were compatible with the conditions of those times. The rise of Buddhism, too, left its significant footprint on the Varna system's legitimate continuance in renewed conditions of life. Thus, soulful adherence to Varna duties from the peak of Vedic menses eventually macerated to subjective makeshift adherence, owing partly to the discomfort in practising Varna duties and partly to external influence.

While the to a higher place impacts were gradual, expeditious withdrawal from Varna rules was made possible by the large-scale influence of western notions of freedom, equality, and freedom. These changes can be observed from 1500 CE correct through the present. For Western nations, rooted in their own cultural background, it made little sense to corroborate of this in their optics antiquated Varna system. Intercepting the Moghul invasion and the nearly-finish sovereignty of multiple Hindu dynasties, British invasion brought with it a fresh worldview based on equality and freedom, incompatible with the Varna system. Massive colonisation, impact of 'cultural imperialism' enforced pregnant alterations on Varna duties. Trade and liberalisation, exchange of civilisation dented the tiny fleck of belief left in continuing the Varna system.

Despite this perpetual decline, the descendants of all four Varnas in contemporary India are trying to reinvent their roots in search of ancestral wisdom. Although the four Varnas have encroached upon each other's life duties, a sense of order and peace is sought and recalled in discourses, community gatherings, and engagement between dissimilar generations. Varna system in contemporary terms is followed either with earnest commitment without reservations and doubtfulness or with ambiguity and resistance arising out of unprecedented external influence and issues of subjective incompatibility. While many citizens practice a diluted version of Varna system, extending its limitations and rigidness to a broader context of Hindu religion, staunch believers still strive and promote the importance of reclaiming the arrangement.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

What Are The Four Varnas,

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1152/caste-system-in-ancient-india/

Posted by: thompsonsaitan.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Are The Four Varnas"

Post a Comment